ABOUT MARY CASSATT

Allegheny City, Pennsylvania United States 1844 -1926

Mary Cassatt’s favorite subjects became children and women with children in ordinary scenes. Her paintings express a deep tenderness and her own love for children.

Born in Allegheny City, Pennsylvania on May 22, 1844. During Post-Civil War America, a graceless Victorian period, Europe attracted droves of artists in search of more romantic sensibilities. Of these exiles, none found herself more at home in France, while remaining essentially American, than Mary Cassatt. As her palette brightened, she became the only U.S. expatriate accepted by the French impressionists, and was invited to show in four of their five independent salons. She even won the admiration of the notorious misognyist Edgar Degas: “There is someone who sees as I do.”

Mary Cassatt’s father, a Pittsburgh banker, had said that he would almost rather see her dead than become an artist. But she proved to have an equally strong will. During the Civil War she studied at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts, then, at the age of twenty-three, traveled extensively in Europe, finally settling in Paris in 1874. Where the other impressionists made a cult of painting out-of-doors, Mary Cassatt rarely left the drawing room. From the new fads for photography and Japanese prints, she introduced cropped images and flattened perspectives into her interiors. She spent the rest of her long life abroad, in unremitting labor at the easel and made herself the best female painter America has produced. Her favorite theme was that of mother and child. Without sentimentalizing the mother-child relationship, she pictured it clearly, and each time new, in its unnumerable facets.

In 1893 she was commissioned to paint part of the decorations at the World’s Fair in Chicago; it was one of the first awards of such importance to a woman. Her oils and pastels regularly fetched six and occasionally, seven figure prices. When a portrait of the artist’s mother was offered at Christie’s in May, 1983, it sold for $1.1 million, establishing a salesroom record for an American Impressionist. Experts long debated Cassatt’s status as an American Impressionist on the grounds that she was an expatriate who did most of her work in France.

Edgar Degas, the women-hating perfectionist, was Cassatt’s closest male friend. He admired her talents, and proceeded to teach her a good deal of his own almost cruelly precise draftsmanship, which has never been surpassed for subtlety. From the Impressionists who became her friends she got the habit of subordinating form, space and texture to the pure play of light, and of giving her pictures a modest, if contrived, sketchiness. Cassatt’s most telling device was her own: she painted plain and sometimes charmless people in classically noble poses, and with the same care that earlier artists lavished on saints and goddesses.

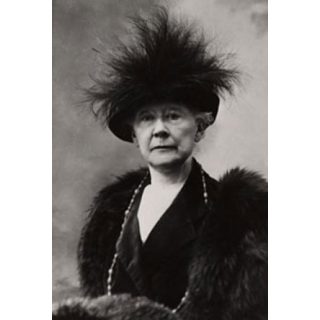

Cassatt was an assertive woman with a penchant for high fashion and high teas. She wasn’t pretty, with a ruddy complexion, snub nose, brown hair and big hands. She was a connoisseur of fashion magazines. At 5 feet, 6 inches, she appeared statuesque, even elegant in high-collared dresses, scarves, feathered hats and parasols. She traveled extensively, braving disease, bed bugs and cold.

Cassatt herself was truly modern for her time. An automobile enthusiast, she bought a Renault in 1906. She was a vegetarian for a while. She attended seances and, while not a particularly religous woman in the conventional sense, she was interested in Spiritualism. The movement was a perfect fit: It preached equality of the sexes and placed high value on children. Cassatt never married, but she lived a full family life until her death in 1926. Her parents, sisters, nephews and nieces were always visiting her villa on the Riviera, her Paris flat or chateau near Beauvais. Even in her old age, she had a prim, acerbic wit, she found Monet too unintelligent, criticized Renoir’s lusty art as too “animal”, scorned the generation of the cubists as “cafe loafers.”

She could also be generous. As she never lacked for money (her brother became president of the Pennsylvania Railroad), she quietly lent much of it to Paris Dealer Durand-Ruel to help back the Impressionists and sold Pissaro (of whom she said “he could have taught stones to draw correctly”) at her tea parties. She was largely responsible for the Havemeyer collection, which stocked New York’s Metropolitan Museum with many of its great El Greco’s, Manets, Courbets and Corots.

“Woman’s vocation in life,” she once said,”is to bear children.” She produced hundreds of children, but they were all on canvas. Around 1910 she began to go blind and had to curtail her work. She died on June 14, 1926 at Chateau de Beaufresne, near Paris.