ABOUT DALE CHIHULY

Tacoma, Washington United States 1941

The Cultural Olympiad of Salt Lake commissioned Chihuly to create a painting and two glass images to commemorate the 2002 Olympic Games.

Dale Chihuly is most frequently lauded for revolutionizing the Studio Glass movement, by expanding its original premise of the solitary artist working in a studio environment to encompass the notion of collaborative teams and a division of labor within the creative process. However, Chihuly’s contribution extends well beyond the boundaries of both this movement and even the field of glass: his achievements have influenced contemporary art in general. Chihuly’s practice of using teams has led to the development of complex, multipart sculptures of dramatic beauty that place him in the leadership role of moving blown glass out of the confines of the small, precious object and into the realm of large-scale contemporary sculpture. In fact, Chihuly deserves credit for establishing the blown-glass form as an accepted vehicle for installation and environmental art, beginning in the late twentieth century and continuing today.

A prodigiously prolific artist whose work balances content with an investigation of the material’s properties of translucency and transparency, Chihuly began working with glass at a time when reverence for the medium and for technique was paramount. A student of interior design and architecture in the early 1960s, by 1965 he had become captivated by the process of glassblowing. He enrolled in the University of Wisconsin’s hot glass program, the first of its kind in the United States, established by Studio Glass movement founder Harvey K. Littleton. After receiving a degree in sculpture, Chihuly was admitted to the ceramics program at the Rhode Island School of Design, only to establish its renowned glass program, turning out a generation of recognized artists.

Influenced by an environment that fostered the blurring of boundaries separating all the arts, as early as 1967 Chihuly was using neon, argon, and blown-glass forms to create room-sized installations of organic, freestanding, plantlike imagery. He brought this interdisciplinary approach to the arts to the legendary Pilchuck School in Stanwood, Washington, which he cofounded in 1971 and served as its first artistic director until 1989. Under Chihuly’s guidance, Pilchuck has become a gathering place for international artists with diverse backgrounds. His studios, which include an old racing-shell factory in Seattle called The Boathouse and now buildings in the Ballard section of the city and in Tacoma, Washington, have become a mecca for artists, collectors, and museum professionals involved in all media.

Stylistically during the past forty years, Chihuly’s sculptures in glass have explored color, line, and assemblage. Although his work ranges from the single vessel to indoor/outdoor site-specific installations, he is best known for his multipart blown compositions. These works fall into the categories of mini-environments designed for the tabletop and large, often serialized forms displayed in groupings on pedestals or attached to specially engineered structures that dominate large exterior or interior spaces.

Chihuly and his teams have created a wide vocabulary of blown forms, revisiting and refining earlier shapes while at the same time creating exciting new elements, such as his recent Fiori, all of which demonstrate mastery and understanding of glassblowing techniques. Earlier forms, such as the Baskets, Seaforms, Ikebana, Venetians, and Chandeliers from the late 1970s through the 1990s, continue to reappear with fresh variations and within new contexts.

Since the early 1980s, all of Chihuly’s work has been marked by intense, vibrant color and by subtle linear decoration. At first he achieved patterns by fusing into the surface of his vessels “drawings” composed of prearranged glass threads; he then had his forms blown in optic molds, which created ribbed motifs. He also explored in the Macchia series bold, colorful lip wraps that contrasted sharply with the brilliant colors of his vessels. Finally, beginning with the Venetians of the early 1990s, elongated, linear blown forms, a product of the glassblowing process, have become part of his vocabulary, resulting in highly baroque, writhing elements.

Chihuly’s work is strongly autobiographical. His fascination with abstracted flower forms, reminiscent for him of his mother’s garden in Tacoma, has been discussed in depth in the literature. Likewise, series such as his Seaforms, Niijima Floats, and even the Chandeliers allude to his childhood in Tacoma, marked by his love of the sea and his recognition of its importance to the economy of the Pacific Northwest. Even in the few instances in which the artist has chosen to respond to earlier historical decorative arts forms, the imagery has personal significance. The Basket series, for instance, developed out of the woven Northwest Coast Indian baskets that Chihuly saw in 1977 with his friend the sculptor Italo Scanga and with the sculptor James Carpenter at the Tacoma Historical Society.

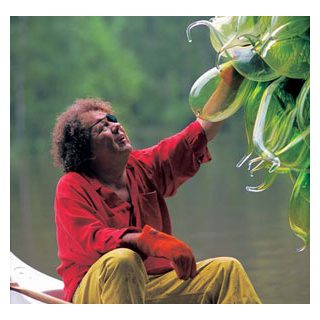

Over the years the artist has created a number of memorable installation exhibitions, including Chihuly Over Venice (1995–96), Chihuly in the Light of Jerusalem 2000 at the Tower of David Museum of the History of Jerusalem (2000), Chihuly in the Park: A Garden of Glass at Chicago’s Garfield Park Conservatory (2001–2), the Chihuly Bridge of Glass in Tacoma (2002), and Mille Fiori at the Tacoma Art Museum (2003). These installations confirm the artist’s sensitivity to architectural context and his interest in the interplay of natural light on the glass that exploits its translucency and transparency. Recent situations have heightened this effect, since the buildings Chihuly has selected as sites for the works have themselves been of glass.

While elements of the earlier installations allude to natural phenomena such as icicles and vegetation, gardens provide the dominant theme in Chihuly’s most recent ones. Sites that include Chicago’s Garfield Park Conservatory and the Franklin Park Conservatory in Columbus, Ohio, as well as future projects at the Atlanta Botanical Gardens and Kew Gardens, London, enable the artist to juxtapose monumental, organically shaped sculptural forms with beautiful landscaping, establishing a direct and immediate interaction between nature and art. Moreover, Chihuly’s most recent installations at the Tacoma Art Museum and at Marlborough Gallery, New York, reveal the artist’s progression toward a logical next direction: installations that are gardens themselves. In a sense, Chihuly has come full circle; now using his mature vocabulary, he captures in these installations the joie de vivre of the plantlike forms of his early neon environments.

A dominant presence in the art world, Dale Chihuly and his work have long provoked considerable controversy as part of the art/craft debate. However, with exhibitions at such major museum venues as the Victoria and Albert in London (2001), there can be little doubt that his lasting contribution to art of our times is an established fact.